Linked Lists are Still Hard

Stephen Brennan • 21 April 2017Kernel development offers a set of challenges that are very different than the ones you would encounter in other types of programming. When you’re new to kernel dev, you hear from lots of sources that you’re gonna have a hard time. But for me, after some initial culture shock, I didn’t feel that uncomfortable. It still felt like user-space C programming. But a few days ago, I finally encountered that bug that made me realize, we’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto.

The bug was introduced by me (of course) into the Multipath TCP protocol implementation. It manifested itself in a rather obvious way: the first socket I created was fine. But when I created a second socket, the kernel would soon freeze up completely. When that happens, there’s nothing you can do but hold the power button (or in my case, kill the VM).

The setup

In my code, I had this idea that I could maintain my own list of MPTCP sockets. This was a bad idea, but I didn’t know it at the time.

Being young and naive, I assumed that the kernel would give me some sort of

notice before it closed and freed the memory associated with a socket. That way,

I could remove it from my list. The solution seemed apparent: I just register a

function named release_sock(), and that should be called before the socket is

freed, right? Right?

Wrong. I still don’t really know what the release_sock() function is there

for, but it is certainly not there to notify me that a socket is about to be

closed! This misunderstanding led to the following sequence of events with my

ill-fated little list.

The bug

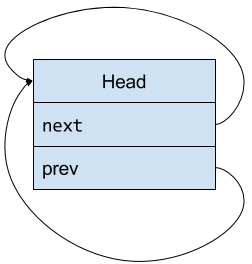

Here’s what my happy little linked list looked like at the beginning:

Like many linked lists in the Linux kernel, it’s doubly linked and circular. Right now it’s empty—the “head” node here simply exists to point to the first and last items.

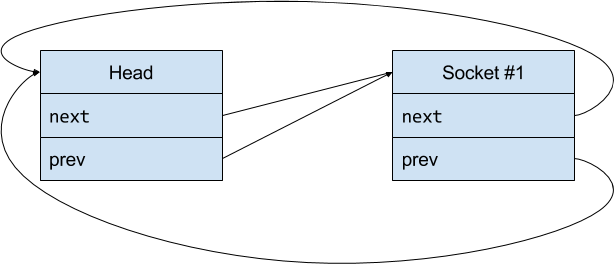

Soon enough, my first MPTCP socket comes along, and I happily add it to my linked list:

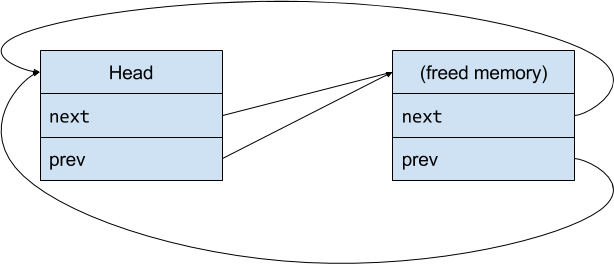

But eventually, this socket is closed, and the memory consumed by it is reclaimed. Unfortunately, nobody ever thought to tell me about it, so now my list looks something like this:

In the world of C, this sort of thing is run-of-the-mill. If you free up memory without cleaning up pointers to it, you’re going to have problems. But what happens next will blow your mind1! In order to understand it, we’re going to take a quick diversion into memory allocation.

Hey, Slab!

In large software systems, you need to allocate plenty of memory. Most of the

time, you use the malloc() or calloc() functions for that, and you don’t

think about the nitty-gritty. But memory allocation is a tricky subject, because

it’s a balancing act.

Memory allocators have a good deal of memory available to them, and they have to be able to respond to requests that say “give me at least X bytes of memory”2. They could respond quickly, by handing over the first available piece of free memory big enough to satisfy a request. But as memory of different sizes is freed, the allocator will run across fragmentation, where it has lots of “holes” of free memory, but none of them are very large. It may have enough total free memory to satisfy some requests, but not enough of it is contiguous. Even if it does have a piece of contiguous memory big enough, it will probably end up searching through a lot of small holes before it can find a big enough free region, and this will hurt performance.

The allocator could try to be smart about it, and group the allocations by size.

The trouble here is that, without knowing the application, the allocator has no

way of knowing what sort of data structures it will use, and so it has no idea

how much memory it should dedicate to different size allocations. In other

words, malloc() is hard.

The Linux kernel is a (very) large software system, and it needs to allocate lots of memory. It uses some data structures an awful lot: for example, the data structure that represents a socket. While it could rely on a general purpose memory allocator to provide this memory, it uses a much smarter solution: a slab allocator!

When you know you’ll be using a lot of a particular data structure, and you know its size ahead of time, you can sidestep a lot of the headaches of allocation with a slab cache. This means that you’ll pre-allocate a lot of blocks of memory (“slabs”) of the correct size, and hold them in a list. When you need one, you simply grab the first one from the list. When you’re done with it, you just return it to the list. If the list gets too small, you can ask the general purpose allocator for more “slabs”, and you can give some back if you have too many. This way you have instant allocation and freeing, and you avoid the fragmentation issues of a general purpose allocator.

Back to the bug

It turns out that MPTCP sockets are allocated using a slab cache. I found this out early on, but forgot about it nearly as soon as I found out.

I remembered much too late.

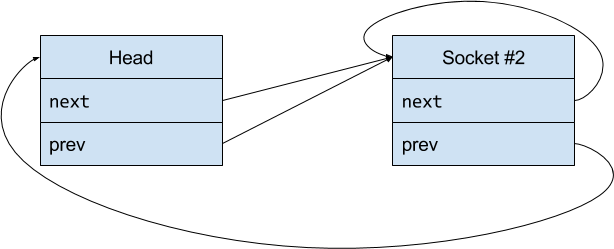

After that first socket was freed (returned to the slab cache), I created a new one. The wonderful slab allocator handed me the first one from its list, which happened to be the exact same piece of memory as the first socket.

I added it to the linked list, a second time. Disaster resulted:

Carnage, bloodshed, and misery! The CPU weeps in anguish, and the memory bus gnashes its teeth. How could this horrific situation happen? Let’s see what the Linux kernel does when you add to a linked list:

// insert new in between prev and next (slightly simplified)

static inline void __list_add(struct list_head *new

struct list_head *prev,

struct list_head *next)

{

next->prev = new;

new->next = next; // (!)

new->prev = prev;

prev->next = new;

}

Quite standard really. If you insert new in front of itself, then the marked

line of code will set its next pointer to itself.

Now, next time you try to iterate through the linked list, you will find yourself in an infinite loop. What’s worse, if you try to be smart and protect this list with a lock of some sort, you will find that every other thread hoping to read or write that list will deadlock too, waiting for your infinite loop to stop.

Debugging

This one kept me up until 3AM. In hindsight, every bug looks simple, and when I figured it out, I was embarassed that it took me so long. I went down a lot of rabbit holes in my investigation, before I brought out the big guns: GDB.

Thanks to my current setup, I can actually use GDB to pause the kernel, step through code, and even evaluate expressions. It’s a feeling of supreme power when you realize that you have, essentially, a C interpreter running within the context of a kernel!

Anyhow, once I zeroed in on the problem, I was able to look at the linked list pointers in short order, and with a little diagramming the problem was quickly revealed. I guess the moral of this story is that tools are excellent, and you should probably use them. Also, be careful of linked lists.

Footnotes

Stephen Brennan's Blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License